Every year I get to about this point in the Advent season and I feel exhausted, almost as though the “reason for the season” is slipping by. Before I was a priest, I was a professional musician, and the old adage that December pays for January and February’s rent is not really an adage at all, it is a lived reality. December, and Advent with it, has always been the busiest season.

And yet, the Church has always given me a gift at this point in Advent, often wrapped in music.

Since my late teens, I have prayed the offices of Morning and Evening Prayer (and, on a good day, Compline). These rhythms have carried me through much of my life. It was here that I first came to know the O Antiphons. For me, they are one of those treasured places of stillness as we approach the final, shimmering days of Advent.

Each year, from 17–23 December, the Church sings these ancient prayers: seven days, seven names, seven windows into who Christ is, and who Christ will be for the world.

Over the coming week, I thought I would reflect each day on the O Antiphon appointed for that day. But first: what exactly are they, and why do they matter?

The “O…” what?

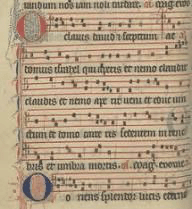

The Great O Antiphons date back to at least the sixth or seventh century. Rooted in the monastic tradition, they were sung at the beginning and end of the Magnificat during Evening Prayer, as the Church counted down the final days before Christmas. While melodies and practices have varied across time and tradition, these seven antiphons are remarkably universal.

Each antiphon begins with “O…” and then names Christ using a title drawn from the Hebrew Scriptures: Wisdom of God, Root of Jesse, Key of David. These are not names invented by the early Church, but inherited, the longings, metaphors, and hopes of Israel carried forward into Christian prayer.

And beautifully, in Latin, the first letters of the seven titles, read backwards, form an acrostic: ERO CRAS – Tomorrow I will come.

Whether this was intentional or a grace discovered later, it perfectly captures the ache of Advent, where longing is stretched toward promise.

Many of us have encountered the antiphons through the hymn O Come, O Come, Emmanuel, which paraphrases them. Others know them through plainchant in religious communities, through Evensong, or through modern choral settings that shimmer with their own interpretations of these ancient words.

Why This Matters to Me

Much of my life has been spent in rehearsal rooms, concert halls, choir stalls, and at sanctuary steps as a cantor. I have been a musician for as long as I can remember, first as a young choral singer, then as a trained professional, and now as a priest.

Throughout Advent and Christmas, I have sung many versions of the O Antiphons. In parish churches, wrapped inside the familiar longing of O Come, O Come, Emmanuel. In masses, where I am most at home singing Marty Haugen’s My Soul in Stillness Waits, threading the antiphons through the eucharistic liturgy. In cathedrals and concert halls, ringing out James MacMillan’s O Radiant Dawn, an explosion of light in musical form. And in the haunting stillness of the plainsong O Radix Jesse, where the air seems to thin and deepen at the same time.

These antiphons lived in my body long before I ever studied their history or understood their theological depth. They taught me how to pray before I knew I was praying.

And, of course, they sit alongside the Magnificat – Mary’s great song of reversal and hope that the Church sings daily. How powerful it is that, each day, we are called as the Church to sing this radical hymn of praise and subversion. The O Antiphons frame her words: the voice of a young woman naming a kingdom not yet fully seen, but deeply trusted.

Music has allowed me to enter that hope again and again.

Perhaps that is why these seven names still feel so alive to me.

They are not abstract titles; they are voices I have sung, places I have prayed, and longings I have breathed in harmony with others.

Why Names Matter

In Scripture, names reveal calling, character, and promise. To name is not merely to label, but to recognise.

The O Antiphons invite us to do just that, to behold the fullness of Jesus, not only as the child of Bethlehem, but as the one whispered about through centuries of prophecy and desire.

These titles are like facets of a diamond, turning the light so that we glimpse Christ from different angles.

They allow us to pray with the Church of the Old Testament: waiting, yearning.

They allow us to pray with the Church of the New Testament: recognising the One who fulfils ancient promises not in abstraction, but in flesh and vulnerability.

Each “O…” is a plea.

Each is a cry of the heart.

Each ends with the imperative: Come.

A Practice of Yearning

To pray the antiphons is to invite Christ into our need.

To call upon his names is to remember who he is.

And to hear “Tomorrow I will come” whispered back to us – here, now – is to rest again in the promise at the heart of Advent.

17–23 December…

So, this is an invitation, if you would like to join me on this journey through the O Antiphons. Each day I’ll be posting a short reflection on one of these ancient names of Christ.

I hope you’ll journey with me.

Come, Lord Jesus.

Come to us in wisdom, in freedom, in light, in peace.

Come, Emmanuel.

I will try to post a musical version of the O Antiphons to go alongside what I have written each day. Today I share something that reflects the O Antiphons. It is called “My Soul in Stillness Waits” by Marty Haugen, an American Composer of Liturgical music. Here, the O Antiphons are woven alongside Psalm 95.

Leave a comment