This Lent, here at St. Andrew’s and in accross our partnership, we continue our series Keeping Holy Time, where we have been exploring why do we do what we do in Lent and holy week, and by engaging with it more deeply ahead of time we can be more able to enter into the mystery and joy of this most Holy time.

And this week we are going to unpack Palm Sunday:

Wondering together

Why palms?

Why procession?

Why this strange collision of joy and sorrow that we call Palm Sunday?

Now our lectionary readings today whisper something of it, but clearly not directly.

(Here are the lectionary readings in you want to read them this week: Genesis 12:1–4a | Psalm 121 | John 3:1–17)

In Genesis, Abram is called to leave – to step into a journey he does not yet understand. Here we find parallels particularly for the disciples as they find a donkey and go into Jerusalem with Jesus.

And in John’s Gospel, Jesus tells Nicodemus that God so loves the world that he gives himself for it.

These encourage us to think about

Journey.

Self-giving love.

And Palm Sunday gathers all of those themes.

I wonder what you think and feel about Palm Sunday: processions, shouts of Hosanna, welcoming a king, only to then return to church, where we read for the first time in Holy Week the Passion reading of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

For almost ten years as a family we lived and worked in Vancouver, in an area called the Downtown Eastside.

It was a remarkable place – and a tough place.

At that time it was the poorest postcode in Canada.

With the highest open drug use.

Profound beauty and profound pain sitting side by side.

I learnt more there about myself, about humanity, and about God than almost anywhere else I have lived.

The church where we served stood dominant in stature and beauty in the midst of that complicated community. A bastion of inclusive Anglo-Catholic worship that drew people from across the city and also the local community.

Those involved in the murky world of drugs, worshipped alongside high court judges, sex workers knelt at the altar with professors of English. It was raw and also a little otherworldly. But the one thing you absolutely could not do there was pretend.

When people are living so close to the edge, inauthenticity can be spotted a mile off -and it will be called out. It can be humbling.

You had to be real.

And whenever I picture Christ on a donkey, I often think – the folk of the Downtown Eastside would have known him.

Because it was authentic.

Humble.

Exposed.

A little absurd, perhaps.

But real.

Every Palm Sunday, we would process through that neighbourhood – a quirky carnival band all dressed in white led us, incense swung and billowed as we walked, colour and beauty of the vestments in all its Anglo-Catholic glory. It was carnival and chaos and beauty and faith woven together.

People would stop.

Some would laugh.

Some would join.

Some would simply watch.

And then we would return to the church.

The doors would close.

The atmosphere would shift.

Holy Week had begun.

The Hosannas would fade.

And like we do here at St Andrew’s – and in churches throughout the world – we would stand and listen to the Passion Gospel.

Palm Sunday is a day of extremes.

And that is not accidental.

In the fourth century, a woman, most likely a nun named Egeria, travelled to Jerusalem. She left us a diary – not a theology book, but a travel journal – describing how Holy Week was kept there all those years ago.

She calls it “The Great Week.” (This is still what Orthodox Christians call it.)

And what she describes is astonishing.

The people gathered on the Mount of Olives.

They listened to Scripture.

They sang psalms.

Children were carried on shoulders.

Elderly people were accommodated.

And then, at five o’clock, the Gospel of the children waving branches was read.

And they began to walk.

Down the Mount of Olives.

Through the city.

All the way to the Anastasis – the place of Resurrection.

They did not simply hear the story.

They walked it.

They sang it.

They inhabited it.

Palm Sunday was not an idea.

It was an embodied drama.

Holy Week was never meant to be rushed.

It was meant to be entered.

And what is remarkable is that what happened in 4th century is incredibly similar to what we know do in 2026 here in London and across the world. The re-living, re-loving of the story continues.

And that matters.

Because when Jesus rides into Jerusalem, he is not staging a sentimental parade.

He is enacting Zechariah’s prophecy – the king who comes riding on a colt.

But not a war horse.

A king of peace.

A king whose victory will not come by the sword.

A king whose throne will be a cross.

The crowd sings Psalm 118:

“Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!”

But that psalm is not just about welcome.

It is about sacrifice.

“Bind the festal procession with branches, up to the horns of the altar.”

The king who enters the city is going up to the altar.

And the offering will be himself.

Palm Sunday is not naïve joy.

It is the beginning of surrender.

And soon we will arrive at Palm Sunday

We will wave palms.

We will sing Hosanna.

We will perhaps smile.

And then we will stand and hear betrayal.

Violence.

Abandonment.

A cross.

Why do we do that?

Because faith that only sings Hosanna will not survive Good Friday.

Because Lent is a journey into the self-giving love of God.

Palm Sunday tells the truth:

The same crowd can shout “Hosanna!” and “Crucify!”

The human heart is capable of both and that focuses our minds in the deeply humbling and painful truth of life.

And Christ rides toward us anyway.

Humble.

Exposed.

Real.

In the lectionary this week, we hear in Genesis the call for Abram to step into a journey.

Palm Sunday calls us to step into one too.

That we too, may enter into the Great Week.

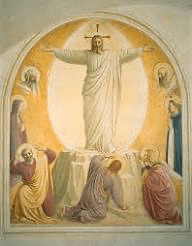

The Church gives us these days of Holy Week and Easter not so that we can observe them from a distance, but so that we can enter them.

To come on Maundy Thursday and kneel.

To keep watch at the altar of repose.

To stand at the foot of the cross on Good Friday.

To sit in the silence of Holy Saturday.

To come to the fire of Easter.

Egeria’s community walked the story over 1600 years ago

We are invited to do the same.

Because Holy Week is not something we consume.

It is something that consumes us.

So, in a few short weeks we too will wave our palms, let us not rush.

Let us not treat this as a liturgical costume change.

Let us allow the joy and the sorrow to sit side by side.

Carnival and chaos and beauty and faith.

Let us be real.

Because Christ is.

As you journey through Lent, let encourage one another not to stand at a distance.

Enter the drama.

Walk the story.

Keep Holy Time.