“The cornerstone making both one”

“O King of the nations, and their desire, the cornerstone, who makes both one: Come and save man, whom you formed from clay.“

For many of us, it carries the weight of disappointment: leaders who divide rather than unite, systems that privilege some and crush others, voices that grow louder while compassion grows thin — even dismissed as weakness. Against this backdrop, we dare to pray O Rex Gentium: O King of the nations. Not ruler of one people, one ideology, or one border, but of all.

And not a king imposed by force, but one named as the desire of the nations.

That phrase is striking. Even where Christ is not named, the longing he fulfils is present: the ache for justice, the hope for peace, the yearning to belong without fear. These desires cross cultures, languages, and histories. They surface in protest and in prayer alike. Advent recognises them as holy longing, and dares to say they find their centre in Christ.

Yet this kingship is defined not by dominance, but by architecture.

“The cornerstone making both one.” In ancient buildings, the cornerstone determined the alignment of everything else. Get it wrong, and the whole structure becomes unstable. Get it right, and walls that might otherwise pull apart are held in relationship to one another.

Paul draws on this image in Ephesians, speaking of Christ as the one who breaks down dividing walls, particularly between those we might define as insiders and outsiders. The cornerstone does not erase difference; it holds difference together. Unity here is not uniformity, but reconciliation.

This is the kingship Advent places before us.

We wait for a king who does not exploit division, but heals it.

A king whose authority is not threatened by plurality.

A king whose reign makes space for many stories, while drawing them towards justice and peace.

I don’t think I can write about O Rex Gentium without naming the rise of nationalism I am witnessing within Christianity here in the UK but with a particular perniciousness in England, a phenomenon not confined to this country, but visible across the globe. There is a pervasive tide advancing in which the language and symbols of Christianity are being claimed in the service of nationalism and exclusion. Recently I read the stark observation that “the far right have parked their tanks on the lawn of the Church of England” (Observer, 14 December 2025). It is an image that unsettles precisely because it names something many of us sense but struggle with and the absolute fear this brings to so many.

This vision could not be further from the Christ we name as O Rex Gentium.

The King of the nations is not claimed by one people, one culture, or one political project. He is not enthroned through dominance or defended by fear. Instead, this King is the desire of all nations, the one who draws rather than coerces, who gathers rather than divides. Formed from the same clay as all humanity, Christ stands in radical solidarity with the whole human family, not elevating one group over another, but revealing the deep belonging of all.

To invoke Christ as O Rex Gentium is therefore to resist every attempt to bend Christianity into a tool of exclusion. It is to proclaim a kingship that dismantles walls rather than fortifies them, that refuses the false safety of nationalism in favour of the costly, vulnerable work of reconciliation. This King does not reign by narrowing the circle of who belongs, but by widening it until all are gathered into one.

And then the antiphon grounds this vast, cosmic vision in something utterly ordinary:

“Come and save the human race, which you fashioned from clay.”

Clay is fragile. Clay cracks when it dries. Clay needs water and care. To speak of humanity as clay is to remember both our dignity and our vulnerability. We are shaped by God’s hands, and easily broken.

This prayer refuses to spiritualise salvation. It remembers bodies. Lives. Earth. The stuff of creation. The king we await does not hover above humanity, but kneels in the dust and works with it. In Christ, the one through whom all things were made enters fully into what it means to be human; limited, dependent, embodied.

There is humility here too.

If we are clay, then none of us is self-made. None of us stands above another. This antiphon quietly dismantles hierarchies of worth and reminds us that every person; refugee and ruler, neighbour and stranger, it shares the same origin and the same need for grace.

To pray O Rex Gentium is to ask not only for rescue, but for re-ordering: for a world rebuilt around a different cornerstone, and for our own lives to be realigned where they have bent towards fear, pride, or despair.

As Advent draws close to Christmas, this antiphon widens our gaze. The child we await belongs not to one nation alone, but to the whole human family. His coming is not a private comfort, but a public hope.

And so we pray, with clay-stained hands and expectant hearts:

come and save us – all of us.

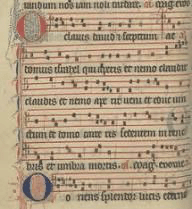

Today’s musical offering comes from the Polish composer Paweł Łukaszewski, whose setting of the O Antiphons is quite new to me. There is a sense restraint in his writing, a sense of listening as much as proclaiming, that feels particularly fitting for O Rex Gentium. The music does not rush to resolution; it holds tension gently, allowing longing, fragility, and hope to coexist. In a world strained by division, this setting sounds like a prayer that refuses force, trusting instead in patient gathering of voices held together, like stones aligned around a true cornerstone.

O King of the nations,

desire of every heart,

cornerstone of a divided world:

re-align our lives with your justice,

soften what has hardened in us,

and remake us, fragile clay,

into a dwelling place of peace;

for you gather all things into one,

and your kingdom has no borders.

Amen.